Children's Crusade

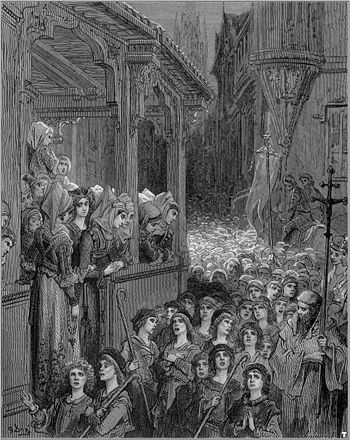

The Children's Crusade is the name given to a variety of fictional and factual events which happened in 1212 that combine some or all of these elements: visions by a French or German boy; an intention to peacefully convert Muslims in the Holy Land to Christianity; bands of children marching to Italy; and children being sold into slavery.

A study published in 1977[1] cast doubt on the existence of these events and many historians now believe[2] that they were not (or not primarily) children but multiple bands of "wandering poor" in Germany and France, some of whom tried to reach the Holy Land and others who never intended to do so. Early versions of events, of which there are many variations told over the centuries, are largely apocryphal.

Contents |

Version of events

Traditional

The long-standing view of the Children's Crusade, of which there are many variations, is some version of events with similar themes.[2] A boy began preaching in either France or Germany claiming that he had been visited by Jesus and told to lead a Crusade to peacefully convert Muslims to Christianity. Through a series of supposed portents and miracles he gained a considerable following, including possibly as many as 30,000 children. He led his followers south towards the Mediterranean Sea, in the belief that the sea would part on their arrival, allowing him and his followers to march to Jerusalem, but this did not happen. Two merchants gave "free" passage on boats to as many of the crusading poor (which most likely included a minimal number of children) as were willing. They were then either taken to Tunisia and sold into slavery, or died in a shipwreck on San Pietro Island off Sardinia during a gale. According to most accounts, many of the poor and elderly failed to reach the sea before dying or giving up from starvation and exhaustion. Scholarship has shown this long-standing view to be more legend than fact.

Modern

According to more recent research there seem to have actually been two movements of people (of all ages) in 1212 in Germany and France.[1][2] The similarities of the two allowed later chroniclers to combine and embellish the tales.

In the first movement Nicholas, a shepherd from Germany, led a group across the Alps and into Italy in the early spring of 1212. About 7,000 arrived in Genoa in late August. However, their plans did not bear fruit when the waters failed to part as promised, and the band broke up. Some left for home, others may have gone to Rome, and some may have travelled along the coast to Marseilles, where they were probably sold into slavery. Few returned home and none reached the Holy Land.

The second movement was led by a 12 year old French shepherd boy named Stephen of Cloyes (a village near Châteaudun), who claimed in June that he bore a letter for the king of France from Jesus. Attracting a crowd of over 30,000 he went to Saint-Denis, where he was seen to work miracles. On the orders of Philip II, on the advice of the University of Paris, the crowd was sent home, and most of them went. None of the contemporary sources mention plans to go to Jerusalem.

Modern explanation

|

|

|||||

Recent research suggests the participants were not children, at least not the very young. The confusion started because later chroniclers, who were not witness to the events of 1212 and who were writing 30 years or more later, began to translate the original accounts and misunderstood the Latin word pueri, meaning "boys", to mean literally "children". The original accounts did use the term pueri but it had a derogatory slang meaning, as in calling an adult man a "boy" can be condescending.[3] In the early 13th century, bands of wandering poor started cropping up throughout Europe; these were people displaced by economic changes at the time which forced many poor peasants in northern France and Germany to sell their land — they were often referred to as pueri in a condescending manner. This mistaken literal interpretation of pueri as "children" gave rise to the idea of a "Children's Crusade" by later authors who found the story too good not to be true, particularly with so much public support and interest in crusading. Within a generation or two after 1212, the idea of children going on crusade became ingrained in history, retold countless times over the centuries with many different versions, and only in the 20th century has the myth been re-examined by looking at the earliest sources.

Historiography

Sources

According to Peter Raedts, professor in Medieval History at the Catholic University of Nijmegen, there are only about 50 sources from the period that talk about the crusade, ranging from a few sentences to half a page.[1] Raedts categorizes the sources into three types depending on when they were written:

- Contemporary sources written by 1220[1]

- Sources written between 1220 and 1250 (the authors could have been alive at the time of the crusade but wrote their memories down much later)[1]

- Sources written after 1250 by authors who received their information second or third hand.[1]

Raedts does not consider the sources after 1250 to be authoritative, and of those before 1250, he considers only about 20 to be authoritative. It is only in the later non-authoritative narratives that a "children's crusade" is implied by such authors as Vincent of Beauvais, Roger Bacon, Thomas of Cantimpré, Matthew Paris and many others.

Historical studies

Prior to Raedts' 1977 study, there had only been a few historical publications researching the Children's Crusade. The earliest were by Frenchman G. de Janssens (1891) and German R. Röhricht (1876). They analyzed the sources but did not analyze the story. American medievalist Dana Carleton Munro (1913–14), according to Raedts, provided the best analysis of the sources to date and was the first to significantly provide a convincingly sober account of the Crusade sans legends.[4] Later, J. E. Hansbery (1938–9) published a correction of Munro's work, but it has since been discredited as based on an unreliable source.[1] German psychiatrist Justus Hecker (1865) did give an original interpretation of the crusade, but it was a polemic about "diseased religious emotionalism" that has since been discredited.[1]

P. Alphandery (1916) first published his ideas about the crusade in 1916 in an article, which was later published in book form in 1959. He considered the crusade to be an expression of the medieval cult of the Innocents, as a sort of sacrificial rite in which the Innocents gave themselves up for the good of Christendom; however he based his ideas on some of the most untrustworthy sources.[5]

Adolf Waas (1956) saw the Children's Crusade as a manifestation of chivalric piety and as a protest against the glorification of the holy war.[6] H. E. Mayer (1960) further developed Alphandery's ideas of the Innocents, saying children were the chosen people of God because they were the poorest, recognizing the cult of poverty he said that ""the Children's Crusade marked both the triumph and the failure of the idea of poverty."[7] Giovanni Miccoli (1961) was the first to note that the contemporary sources did not portray the participants as children. It was this recognition that undermined all other interpretations,[8] except perhaps that of Norman Cohn (1971) who saw it as a chiliastic movement in which the poor tried to escape the misery of their everyday lives.[9] Peter Raedts' 1977 analysis is considered the best source to date to show the many issues surrounding the Children's Crusade.[2]

Popular accounts

Beyond the scientific studies there are many popular versions and theories about the Children's Crusades. Norman Zacour in the survey A History of the Crusades (1962) generally follows Munro's conclusions, and adds that there was a psychological instability of the age, concluding the Children's Crusade "remains one of a series of social explosions, through which medieval men and women—and children too—found release".

Steven Runciman gives an account of the Children's Crusade in his A History of the Crusades.[10] Raedts notes that "Although he cites Munro's article in his notes, his narrative is so wild that even the unsophisticated reader might wonder if he had really understood it." Donald Spoto, in a book about Saint Francis of Assisi, said monks were motivated to call them children, and not wandering poor, because being poor was considered pious and the Church was embarrassed by its wealth in contrast to the poor. This, according to Spoto, began a literary tradition from which the popular legend of children originated. This idea follows closely with H. E. Mayer.

In the arts

Works of art specifically and primarily about the Medieval event. Because of the large number of works that reference "Children's Crusade" for various artistic purposes, it is beyond the scope to list them all here, this list is focused on works that are set in in Middle Ages and focus primarily on a re-telling of the events. For other uses see Children's Crusade (disambiguation).

- La croisade des enfants ("The Children's Crusade", 1896) by Marcel Schwob.

- La Croisade des Enfants (1902), a seldom-performed oratorio by Gabriel Pierné, featuring a children's chorus, is based on the events of the Children's Crusade.

- Children's Crusade - a contemporary opera by R. Murray Schafer, premiered by Soundstreams Canada Concerts in partnership with Luminato in Toronto in 2009.

- Cruciada copiilor ( en. Children's Crusade ) (1930), a play by Lucian Blaga based upon the Crusade.

- The Children's Crusade (1958), children's historical novel by Henry Treece, includes a dramatic account of Stephen of Cloyes attempting to part the sea at Marseille.

- The Gates of Paradise (1960), a novel by Jerzy Andrzejewski centres around the crusade, with the narrative employing a stream of counsciousness technique.

- The Death of the Bishop of Brindisi (1963), cantata by Gian-Carlo Menotti, describes a dying bishop's guilt-ridden recollection of the Children's Crusade, during which he questions the purpose and limitations of his own power.

- Children's Crusade, Opus 82, A Ballad for Children's Voices and Orchestra (1968), cantata with music by Benjamin Britten, and words by Bertolt Brecht and Hans Keller.

- "Song of the Marching Children" (1971) by Dutch Progressive rock band Earth and Fire from the album of the same name. The song references the Children's Crusade but does not explicitly mention it by name.

- Crusade in Jeans (Dutch Kruistocht in spijkerbroek), is a 1973 novel by Dutch author Thea Beckman and a 2006 film adaptation about the Children's Crusade through the eyes of a time traveller.

- The Children's Crusade (1973), a play by Paul Thompson first produced at the Cockpit Theatre (Marylebone), London by the National Youth Theatre.

- A Long March To Jerusalem (1978), a play by Don Taylor about the story of the Children's Crusade.

- An Army of Children (1978), a novel by Evan Rhodes that tells the story of two boys, a Christian and a Jew, partaking in the Children's Crusade.

- Lionheart (1987), a historical/fantasy film, loosely based on the stories of the Children's Crusade.

- "Sea and Sunset" (1989), short story by Mishima Yukio.

- Yndalongg (1996), a 10" released by the Austrian musical duo The Moon Lay Hidden Beneath A Cloud features a track based upon the story of the Children's Crusade. The same song is also featured on their 1999 release Rest on your Arms reversed.

- The Fire of Roses (2003), a novel by Gregory Rinaldi

- Crusade of Tears (2004), a novel from the series Journey of Souls by C.D. Baker.

- The Crusade of Innocents (2006), novel by David George, suggests that the Children's Crusade may have been affected by the concurrent crusade against the Cathars in Southern France, and how the two could have met.

- The Scarlet Cross (2006), a novel for youth by Karleen Bradford

- 1212: Year of the Journey (2006), a novel by Kathleen McDonnell

- Sylvia (2006) a novel by Bryce Courtney

- The Children's Crusade (2009) composed by R. Murray Schafer

Footnotes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 Raedts, P (1977). "The Children's Crusade of 1213". Journal of Medieval History 3.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Russell, Frederick, "Children's Crusade", Dictionary of the Middle Ages, 1989

- ↑ See Wiktionary entry for Boy", definition #5, "A lower-class or disreputable man; a worthless person".

- ↑ Munro, D. C. (1913–14). "The Children's Crusade". American Historical Review. 19:516–24.

- ↑ Alphandery, P. (1954). La Chrétienté et l'idée de croisade. 2 vols.

- ↑ Waas, A. (1956). Geschichte der Kreuzzüge

- ↑ Mayer, H.E. (1972). The Crusades

- ↑ Miccoli, G. (1961). "La crociata dei fancifulli". Studi medievali. Third Series, 2:407–43

- ↑ Cohn, N. (1971). The pursuit of the millennium. London.

- ↑ Runciman, Steven (1951). "The Children's Crusade", from A History of the Crusades.

Bibliography

- Frederick Russell, "Children's Crusade", Dictionary of the Middle Ages, 1989, ISBN 0-684-17024-8

- Peter Raedts, "The Children's Crusade of 1212", Journal of Medieval History, 3 (1977)), summary of the sources, issues and literature.

- Chronica Regiae Coloniensis, a (supposedly) contemporary source. From the Internet Medieval Sourcebook.

- The Children's Crusade, from History House